A loan (credit) is “non-performing” when it’s either over 90 days overdue or unlikely to be reimbursed by the client (business or consumer). In this case, credit institutions (e.g., banks) can resort to one of the three following recourses:

- either “work it out” with the customer, e.g., grant a moratorium (postponement), restructure the repayment, discount the loan, etc.;

- take legal action, e.g., foreclose, liquidate or otherwise enforce the guarantees, if any; or

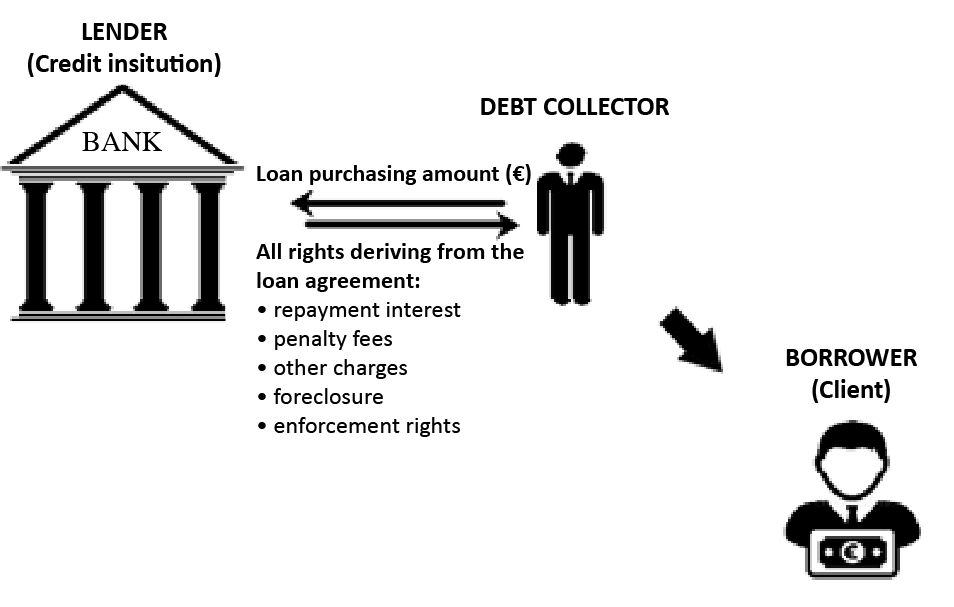

- sell the non-performing loan (NPL) to a debt collector.

Credit institutions very often choose the latter – selling NPLs to debt collectors – as a fast way out: the bank quickly gets a part of the loan back and moves on, while the debt collector substitutes the bank in the contractual relationship (lender – borrower) with the client.

In theory, it all sounds fair and efficient.

©BETTER FINANCE, 2021

However, the reality is very grim for borrowers who cannot repay their loans. First, defaulting on a loan will cause the initial amount to mushroom due to all related penalties, interest, fees, and other charges which must be borne by the borrower. Second, assets (securing the loan) will probably be liquidated below par value, increasing pressure on the borrower.[1] Last, debt collectors are not known for their sympathy when trying to recover the amounts borrowed.

Research from consumer organisations[2] and BETTER FINANCE member organisations far too often points to the heavy-handed practices of debt collectors when dealing with defaulting and distressed borrowers. From harassment to charging excessive fees or speculative profit margins, debt collectors in many EU Member States put consumers who are not able to pay or continue paying their credits in a very stressful and difficult situation.

The Current State of NPLs and the COVID-19 Aftermath

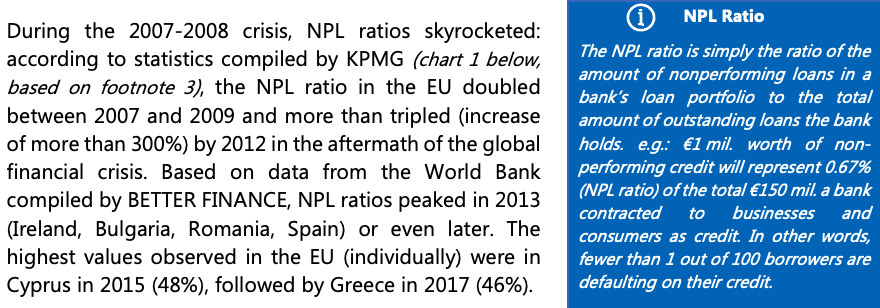

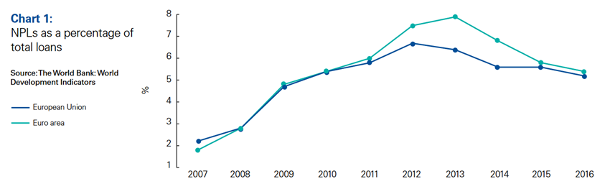

Source: KPMG, 2018 (see footnote)[3]

Recent EU financial policies have been successful in reducing the volumes and ratios of NPLs in the EU. By the end of 2019, the share of NPLs returned to below 5% in 76% of EU Member States. On average, the European Central Bank reported a share of 2.8% of NPLs for the third quarter of 2020 (end of September).[4]

However, the restrictions imposed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic may have significantly affected the capacity of many consumers and businesses to repay their loans. Although 2020 marked a new low for the NPL ratio, it is expected to rise again across the EU once aid measures (e.g., moratoria or forbearance) cease.[5]

What Can Be Done?

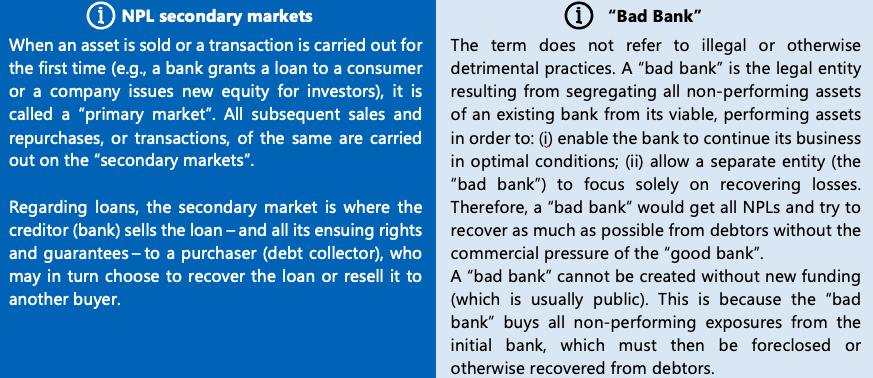

EU financial policy has focused on the macro-side of the NPL issue, essentially aiming to help banks deal with large NPL ratios.[6] Proactively, the European Commission currently attempts to prepare the EU banking sector and Governments for what could hit them in the aftermath of the COVID- 19 crisis through a series of legislative measures such as the NPL secondary markets proposal or by coordinating the set-up and management of national “bad banks”.[7]

While such strategies have merit, they are not sufficient, since distressed banks will reduce their funding (credit) capacity to the economy and also put deposits at risk. Freeing up space on banks’ balance sheets should not be done without enforcing responsible lending practices, financial education and retail saver protection. The measures proposed by BETTER FINANCE hereunder aim to either prevent the build-up of NPLs or to adequately help and protect non-professional debtors when they default on their loans.

RESPONSIBLE LENDING

NPL accumulation can be prevented if credit institutions adhere to the principles of responsible lending such as adequate credit risk assessments and evaluations of guarantees to discern viable from non-viable borrowers.

Even though regulation can afford more flexibility to professionals (the business sector), particular attention should be paid to consumer credit, especially unsecured loans. Consumers should not be encouraged, nor “simply allowed”, to take out credit if it can reasonably be assessed reimbursement may present a problem.

Most importantly, evidence from BETTER FINANCE’s Members also shows that responsible lending should extend to tied third-parties, such as guarantors: on many occasions, creditors or credit purchasers instantly turn to guarantors to enforce defaulting loans, creating more problems than it solves. Responsible lending should also assess the borrower’s guarantors to ensure that they are also creditworthy.

In addition, we believe that banks should be required to take more steps in an effort to find a solution with the debtor. In the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis, many previously viable borrowers have been pushed into default due to restrictions on their professional activity. However, many may still stand a solid chance to pick up and transform a non-performing exposure to a performing one, once the economic conditions are restored. This way, NPL levels can be reduced if creditors first attempt to restructure, offer moratoria/forbearance or even discount the loan for the borrowers, as often happens with credit purchasers. In other words, selling the NPL on the secondary market should only be a measure of last resort. Creditors should always strive and endeavour to turn the loan back into a performing one or settle it with consumers, rather than selling it to the highest bidder to “purge” balance sheets of non-performing exposures.

Moreover, even in those exceptional cases, secondary markets for consumer NPLs should be transparent and should make use of new EU digital platforms for fundraising, such as crowdlending or peer-to-peer lending platforms. This would ensure an adequate level of liquidity, fair price formation mechanisms, objectiveness and the fair treatment of debtors.

Research from consumer organisations and BETTER FINANCE members shows that banks choose to dump NPL portfolios at a 50%-60% discount for secured loans, and as much as 95% - 97% for unsecured loans.[8] This illustrates how transparency on secondary markets for consumer loans is essential to prevent NPLs or reduce their level, since the borrower could, in fact, buy back his or her loan back at such discounted rates.

FINANCIAL EDUCATION and FAIR DISCLOSURE

As highlighted in a 2013 World Bank paper, responsible lending cannot be disconnected from responsible borrowing, which can be achieved through financial education and adequate disclosure on the price and risks of borrowing. Borrowing should not be disincentivised, but adequately presented and advised on. Retail clients need to be made fully aware of the extent of the obligation they are contracting, particularly about the consequences of defaulting on that obligation (repaying the loan). This can be done either at the point of sale, through fair, clear, and not misleading disclosures and prominent warnings of the risks attached, or through financial guidance counselling. In this vein, the High-Level Forum on the Future of the Capital Markets Union Final Report comprises a recommendation on setting up financial guidance centres at national level for the benefit of EU households.

Surveys indicate that the initial place of seeking advice to prevent loan-related risks tends to be family and friends (especially for young people), de facto creating knowledge and awareness disparity between households. Some associations, NGOs and public centres are also present and act as debt advice substitutes to borrowers. Unfortunately, their accessibility remains uneven between Member States. Moreover, too often these auxiliary services or consumer protection bodies accompany people in their disputes and financial education is only achieved on the late, at debt-counselling time. Therefore, in its preventive aspect, financial education must also address the unexpected life events and monetary-related lifestyle of the individual; elements that are not sufficiently put forwards or explained by the provider, both in terms of disclosure and of debt-capacity evaluation (‘reference budgets’). In addition, the Financial Literacy Survey points out that a hazardous path would be for banks to take the lead role in financial literacy education. Indeed, marketing-led financial education could be at odds with the principle of fair and equitable disclosure practices. Therefore, banks should be incentivised in providing practical expertise and guidance towards well-aware citizens, whereas independent financial education will enable self-judgment and evaluation of debt situation or borrowing positions. This should participate in the way forward to mitigate non-performing loans – both for the stability of banks and for the benefit of the contracting population.

RETAIL CLIENT PROTECTION

The existing retail client protection rules at EU and national level are meant to prevent debt collectors (often called “vulture funds”) from creating a detrimental situation for defaulting borrowers, in particular non-professional and distressed ones. However, evidence from BETTER FINANCE’s member organisations shows that this is not the case, and in spite of the risk of hefty fines or licence withdrawals, debt collectors (the new credit purchasers) keep using prejudicial practices against defaulting “sold” borrowers.

Thus, in addition to incorporating the necessary protective safeguards into new legislation on credit services and credit buyers, EU legislation should require EU member states to ensure that their competent national authorities (typically consumer protection authorities) have the necessary resources to adequately supervise and enforce the framework for the protection of retail clients from/against debt collectors.

[1] See Jose Manuel Mansilla-Fernandez, ‘Numbers’, Figure 6, p. 29, in Giorgio Barba Navaretti, Giacomo Calzolari, Alberto Pozzolo (eds.), European Economy: Banks, Regulation, and the Real Sector (1/2017) available at: https://www.bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/European_Economy_2017_1_v1.pdf.

[2] See BEUC, Secondary Market for Non-Performing Loans: The European Commission’s Proposal Is a Bad Deal for Distressed Borrowers (BEUC-X-2018-068) pp. 7-8, available at: https://www.beuc.eu/publications/beuc-x-2018-068_secondary_market_for_non-performing_loans.pdf.

[3] KPMG, ‘Non-Performing Loans in Europe: What Are The Solutions?’ (KPMG, August 2018), Chart 1, page 7, available at: https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2017/05/non-performing-loans-in-europe.pdf.

[4] European Central Bank, Supervisory Banking Statistics: Third Quarter 2020 (January, 2021) ECB, Table T04.02.1, p. 67, available at: https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/ecb/pub/pdf/ssm.supervisorybankingstatistics_third_quarter_2020_202101~9b085b2142.en.pdf.

[5] See Communication from the European Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the European Central Bank: Tackling Non-Performing Loans in the Aftermath of the COVID-19 Pandemic (16 December 2020), COM(2020) 822 final.

[6] See, for instance, the Council of the EU’s Action Plan to Tackle Non-Performing Loans in the EU: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2017/07/11/banking-action-plan-non-performing-loans/pdf; see the Explanatory Memorandum accompanying the Commission’s Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on credit servicers, credit purchasers and the recovery of collateral (14 March 2018) COM(2018) 135 final.

[7] Commission’s Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on credit servicers, credit purchasers and the recovery of collateral (14 March 2018) COM(2018) 135 final.

[8] See BEUC, Secondary Market for Non-Performing Loans, op. cit. (2).