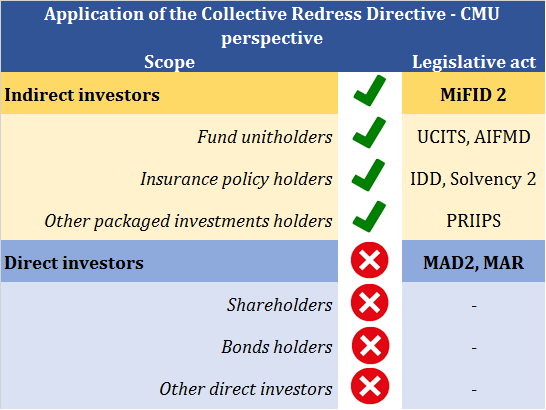

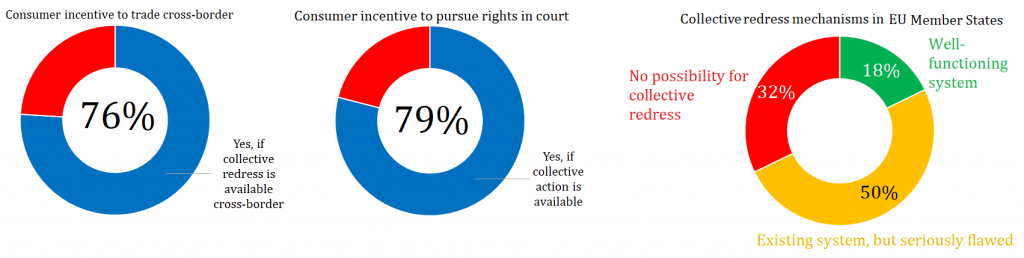

A single market for capital and investments brings a myriad of benefits, but also exposes consumers to cross-border cases of mis-selling of financial products. BETTER FINANCE advocates for a collective redress mechanism that benefits all EU citizens as direct or indirect investors, such as small and individual shareholders, pension fund participants, life insurance policy holders or other financial services users. Read our Collective Redress Booklet for more info.

A proper collective enforcement mechanism for consumers is the founding pillar of a true Capital Markets Union.

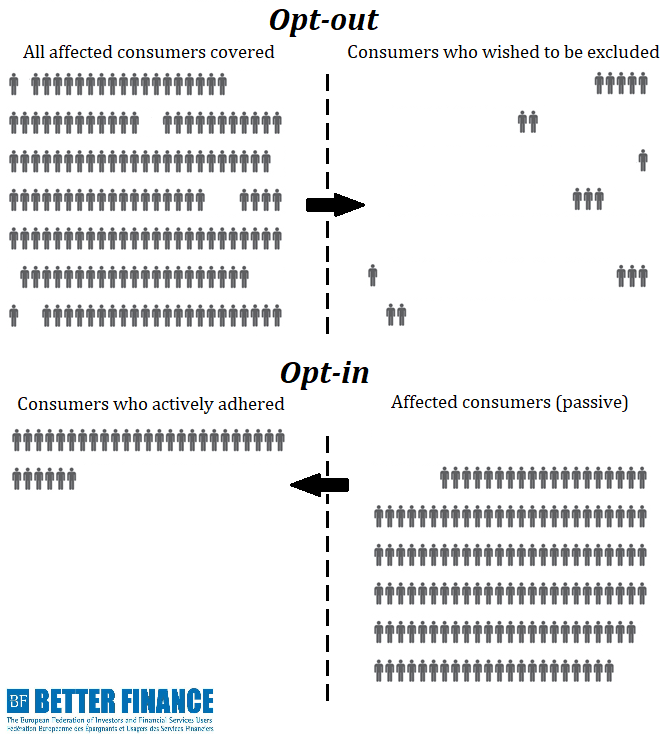

– in the opt-in system, each of the affected consumers must undertake certain procedural actions (write a writ of summons, a claim of adherence, pay judicial taxes) within a defined time-frame (generally, before the first hearing) to be included in the case;

– in the opt-in system, each of the affected consumers must undertake certain procedural actions (write a writ of summons, a claim of adherence, pay judicial taxes) within a defined time-frame (generally, before the first hearing) to be included in the case;

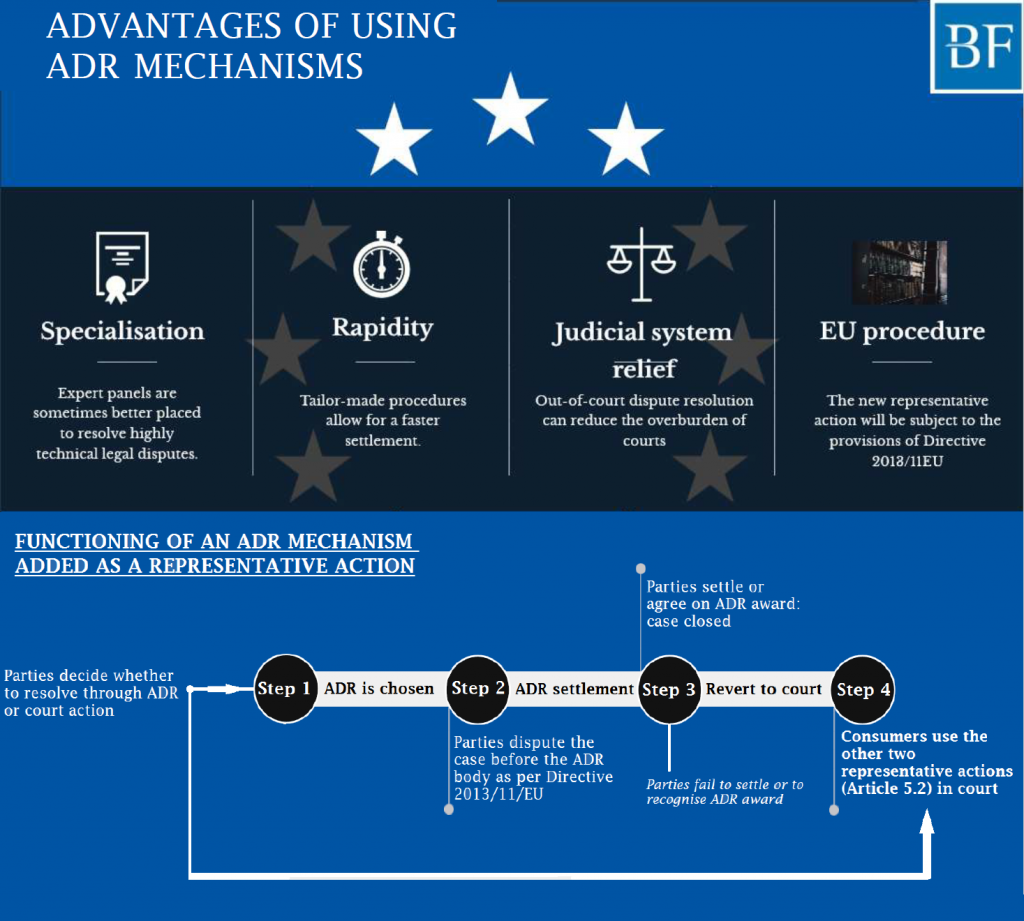

Consumer organisations should be allowed to choose whether to proceed through ADR first or directly with national courts. If a settlement is reached with the trader, it would then be validated by a court and become applicable to all those covered.

Consumer organisations should be allowed to choose whether to proceed through ADR first or directly with national courts. If a settlement is reached with the trader, it would then be validated by a court and become applicable to all those covered.

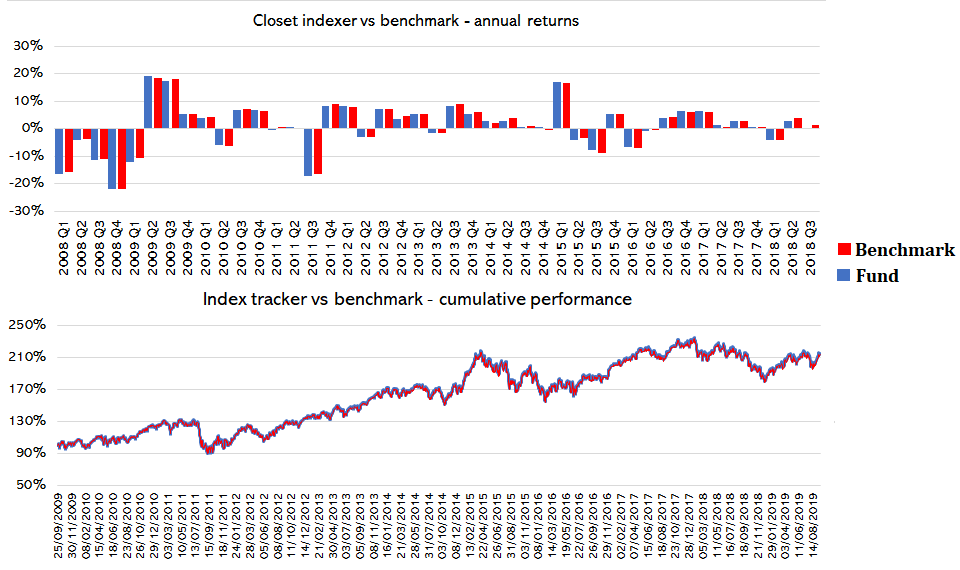

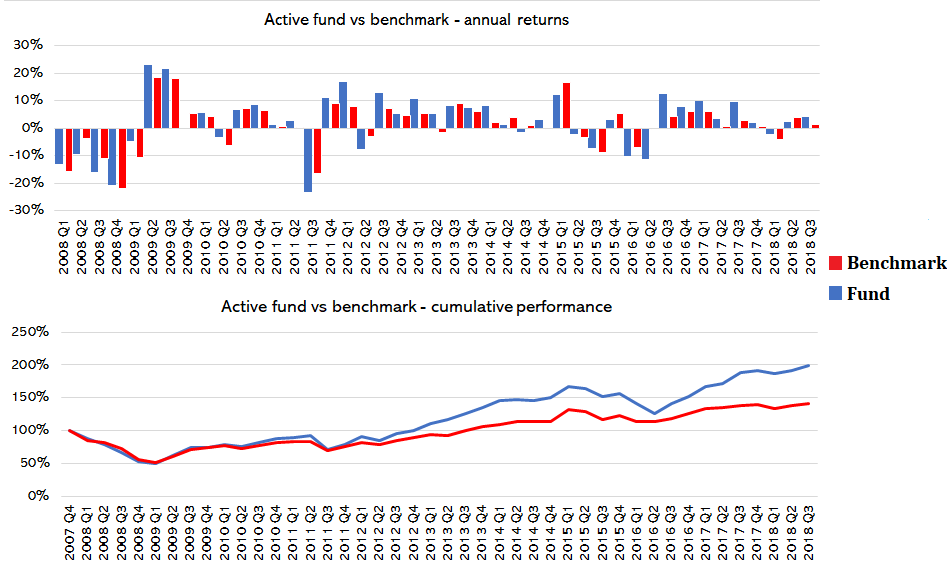

On the left-hand side are the annual returns (first graph) and cumulative returns (second graph) of an actively managed fund (blue) and that of its market index benchmark (red). As apparent, the returns display differences (positive and negative) between the performance of the fund and that of the benchmark from one year to another, while the cumulative performances break-off after a couple of years.

On the left-hand side are the annual returns (first graph) and cumulative returns (second graph) of an actively managed fund (blue) and that of its market index benchmark (red). As apparent, the returns display differences (positive and negative) between the performance of the fund and that of the benchmark from one year to another, while the cumulative performances break-off after a couple of years.